Twelve years of waiting for housing, drainage, and compensation for loss and damage, among other things. These unfulfilled promises by the President of the Republic have plunged the population into a Sisyphean myth, forced to start over again each time the water level rises. Who did what?

By Leocadia Bongben, Adrienne Engono Mussang, and Romulus Dorval Kuissié on their return from the Far North.

Like the modest town of Bethlehem in Judea, which welcomed the Saviour more than 2,000 years ago, the small village of Guirvidig in the Mayo Danay division in Cameroon’s Far North had the privilege of welcoming the President of the Republic, Paul Biya, on 20 September 2012.

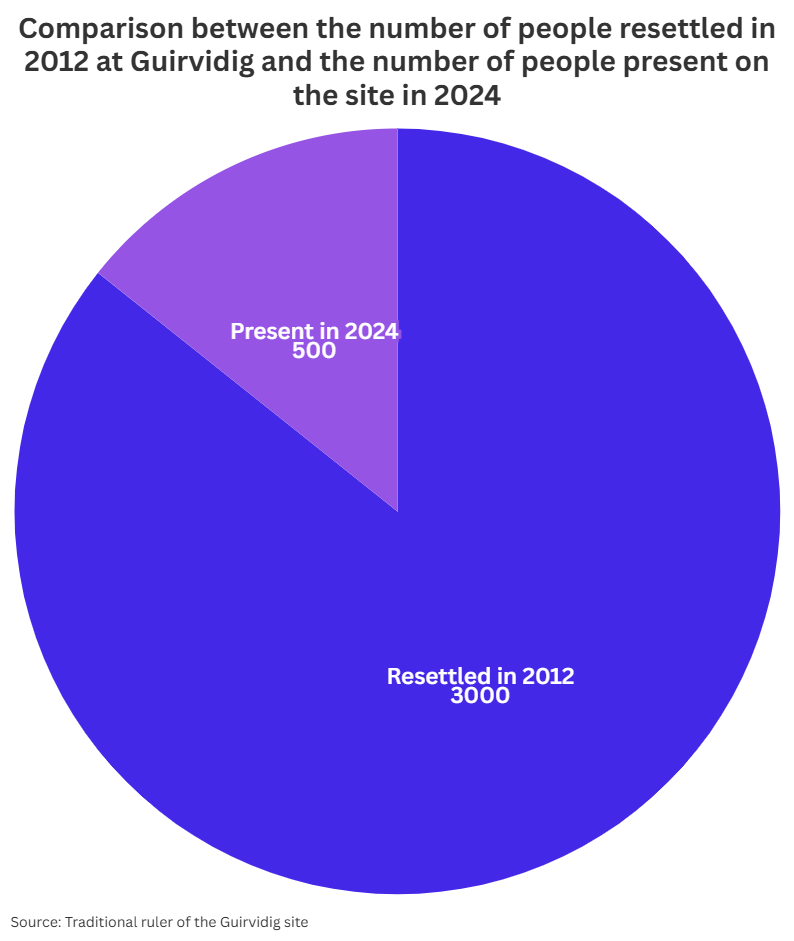

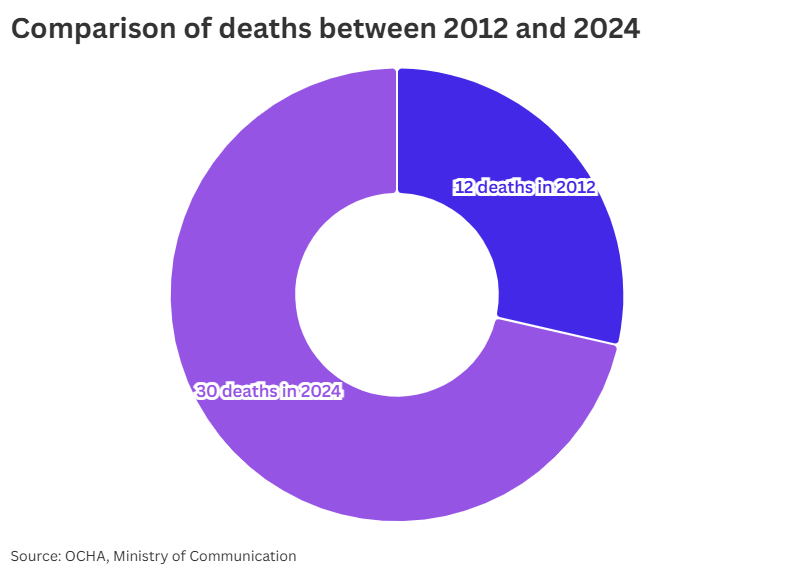

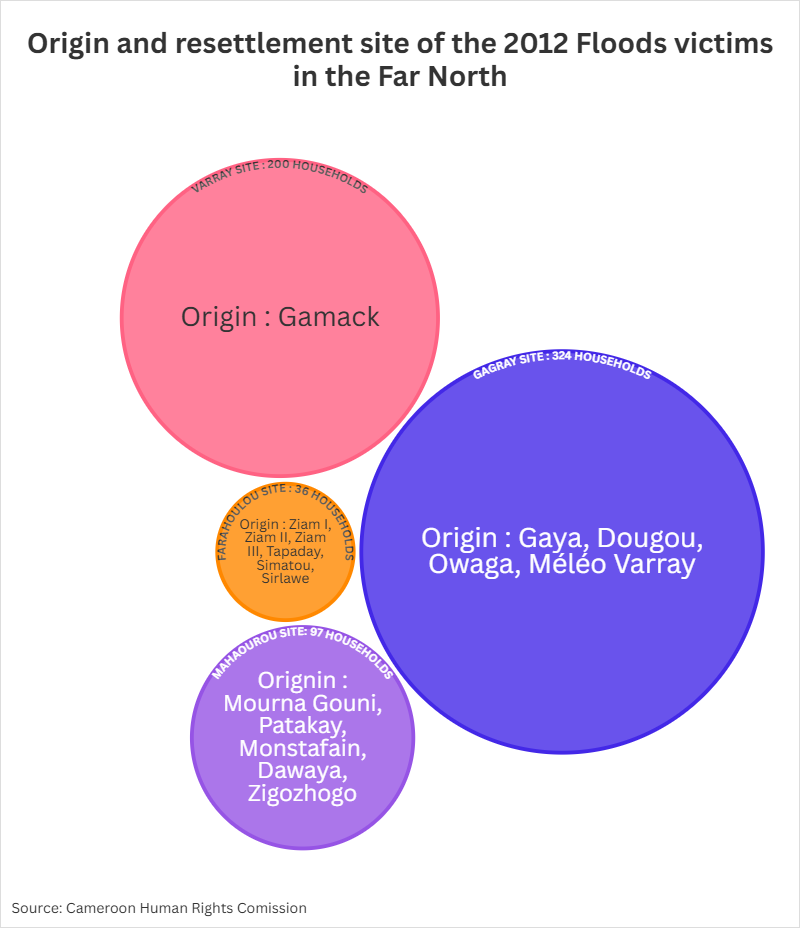

Following the floods, approximately 3,000 disaster victims were quickly relocated to the Farahoulou and Gagraye camps. This abruptly halted their livelihoods. The government said the floods that resulted in the deaths of at least 30 people, marked Cameroon’s most visible evidence of climate change.

‘My presence here is also justified by my desire to confirm that the government is behind you and will be with you. At the end of my visit to the North, I would like to say how touched I was by the kindness and warmth of your welcome, despite the pain (…) The ordeals you have been facing for some time have been painful and tragic, and I salute the dignity and courage you have shown at this difficult time. Speaking particularly to those who have lost a loved one during these sad events, I would ask them to accept my sincere compassion and my most sad condolences, to which I add those of the entire Cameroonian people. It is, of course, with deep emotion that I learned of the misfortune that has befallen several localities in your regions, resulting in major damages of all kinds, the President of the Republic declared in his compassionate speech.

Promises… but no action

Sarke, dark skin, wearing a pair of blue rubber shoes, and clothes that depict their age, sits on a low seat under a tree in the neatly swept courtyard. The 75-year-old father of eight is the leader (Djaouro) of the flood victims who remained in the Farahoulou resettlement site in Guirvidig.

Mr Sarke has a strong memory of these incidents. He is the eldest of the thirty-one families currently living there, out of about 2,000 families relocated to the site during the 2012 flooding.

‘Paul Biya came here in 2012. His Helicopter landed here, and he came to console us because we had lost not only our possessions but also our brothers and sisters in the floods’, recalls Djaouro, this Toupouri son whom we met in Guirvidig on 28 November. The Toupouris are one of the about 250 ethnic groups in Cameroon found in the Far North region.

The village still bears the scars of the 2024 floods, with water puddles here and there, even though the people are returning to their daily activities. Burdened by age, the old man, his brothers, and his sons still remember those they lost to last year’s floods. Sorrow and grief envelop them each time the name of a loved one is mentioned, and that grief is compounded by the unfulfilled promises made by the Head of State.

‘When Paul Biya came, he promised to build a drainage system to limit flooding, but nothing has been done. We had two boreholes here, one of which has broken down. We asked his representatives (Sub-Divisional Officer ), but nothing was done. The President promised us a health center and a school, but we are still waiting.

Some of the victims have returned to the old site, but for people like Sarke, starting all over isn’t an interesting prospect. ” I had lost everything: the ducks, the fields, the crops, my house,” says Sarke. Like the other occupants, he was given around 800 m2. “Only the markers to demarcate our land have been put in place,” he says.

More powerful waves

The year 2024 has been particularly challenging for Mr. Sarke and his family. The floods came again, disrupting their daily lives. No lives might have been lost, but the floodwaters swept away almost everything.

.“Some of us are already struggling to start families, but because of the floods, we lose everything and have to start over again. It’s exhausting. In the flood of 2024, for example, I lost nine goats, and the water always brings us back to zero. We fled our first village for here, so where would we go to start our lives again?’ asks a young man at Guirvidig, whom we also met at the resettlement site donated by the State of Cameroon in 2012.

Despite their ingenuity, the lack of adequate resources to build solid barriers means floods wipe out all their efforts. ‘We try to fight the floods by building protective earthen dykes, but sometimes that doesn’t work because the water comes with great force,’ says the young man.

The same causes produce the same effects

About twenty kilometers from Guirvidig, we met DJONDANDI GOURANDI and his neighbours in the Simatou village, which the floods had hit. Simatou Sinistre is a village in the Maga district derived from SI= Sirata MA= Massa Tou= Toupouri- the three tribes brought by the rice cultivation company SEMRY. They are among the victims of the 2012 floods who have returned from Farahoulou, the resettlement site in Guirvidig.

People resettled in Farahoulou, Guirvidig, have returned to face the everyday difficulty of fighting back floodwaters. “We returned here a few years ago because life was hard. We were far from fertile land, and the SEMRY forced us to leave our villages for here. We decided it would be better to come back and fight the water rather than starve to death,” says the 86-year-old father of 52. They are certain that directing the water will significantly lessen the damage caused by floods. “We’re asking the government to build us canals so we can hold on until the water level rises,” he explains.

Women are forced to ignore the law to play their part

Sarke throws some grains of corn and his chicken and ducks scamper to peck at the food. Selling fuel wood has become a new form of survival.

‘I only manage. I have no farms; I am surviving thanks to my two wives. They cut wood and sell it to ensure our survival; they feed us. In case of illness, although the promised health center does not yet exist, we go to the one far from here,” says Sarke. Thanks to his wives and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) the people are gradually rebuilding their broken lives, but for how much longer?

Women continue to play an important role in the Guirvidig community. Dame Kondi, widowed a few years ago, also engages in the dangerous business of cutting and selling wood at her peril. ‘I have problems with forest guards from the Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife; when they arrest me with the wood I cut fraudulently to survive, they keep me sitting all day in the bad weather, despite my age. They confiscate my machete and the wood. Though they later set me free, on that day, there would be no food for my family. I would return the next day because I have no choice and do not have the means to feed my family. At times I succeed and get away unnoticed. We have no land, not even a farm near our houses,” laments the widow, Kondi.

Every year, census commissions come and go, interviewing the residents of Guirvidig, But nothing is done after that.

‘We don’t get money, houses, or the means to reintegrate. My children go to school thanks to the small businesses I run, such as laundry and small-scale farming (with no arable land) compared to what I earned where I lived before the 2012 floods, it’s not enough, says another head of household.

‘We’re waiting for the promises to be fulfilled. We regularly go to the Sub-Divisional Officer so that he can pass on our grievances’, says Mr SARKE. The young people in the community go to school intermittently. Many of them lack the means to pay for school supplies and fees. Their parents lost everything to the floods.

Prevention… and reaction

According to Sede, the sub-prefect of the Maga district, the government is deploying resources to prevent damage and assist people during disasters. ‘We monitor information from the organizations in charge of meteorology, which we disseminate via the traditional chiefs, to raise awareness among the people,’ explained Mr Sede in an interview with our team.

Newly appointed to this post, he was absent during the 2012 floods and could not comment. Though the people of Simatou say they did not receive anything, even soap, during the 2024 floods, the local authority praises the mobilization of the hierarchy to handle and effectively manage the emergencies faced by the population. This spared Maga from health consequences such as the dreaded cholera and even famine. ‘There is the VIVA Logone project and others that would help the farmers to cultivate crops like rice twice a year. He acknowledged that the Maga district, like the Mayo Danay Division, is a basin that absorbs the waters of the Logone River, the Maga Dam, and the Lake Chad Basin.

The Maga Council also supported the victims by distributing empty bags which the local people filled with earth to build protective dykes. Except that in Guirvidig, as in Simatou, these bags are almost non-existent. Hence, their cries for the Head of State’s ‘high instructions’ to be respected.

So what happened to the Head of State’s 2012 promises?

In 2024, what has been realized? Why? Who took delivery of what? When? What has happened? Questions that sometimes remain unanswered drowned in the opacity that surrounds route-dyke project.

An illusory road dyke?

The construction of the Kousseri-Yagoua road dyke is one of the prescriptions made by President Paul Biya during his visit to Guirvidig on 20 September 2012. ‘I also prescribed short- and medium-term measures including, in particular, the construction of a 330 km road dyke from Gobo to Kousseri’, he had announced.

A feasibility study for the project, financed at a billion francs by the government through the Ministry of the Economy, Planning and Regional Development (MINEPAT), had estimated construction at FCFA 1,000 billion. But until December 2024 (12 years later), the construction of the 15-metre-wide dyke through 60 villages, which was intended to solve the problem of flooding in the region, is still awaited.

GUIBAI GUITAMA, a North-based elite, feels that the government lacks funds, however, he also cites a lack of political will in the construction of the road dam, as other projects are underway elsewhere. ‘The CFAF 1,000 billion required to create the road embankment might be divided into portions,’ he claims.

According to him, building a 330-kilometer-long dam for agricultural, fishing, and population mobility might prevent recurring flooding that disrupts the population. “We trust that the promises will be followed for the benefit of the people and Cameroon as a whole because every development effort and economic activity benefits all Cameroonians. The money donated to flood victims may be put to better use elsewhere,” according to Guibai.

Aboukar Mahamat is a wetlands expert and national coordinator of the NGO Alliance Citoyenne pour le Développement et l’Education à l’environnement (ACEEN). Based in the Far North region, he attended all the community consultation sessions as part of the study, which was conducted jointly by a consortium of Tunisian and Cameroonian consultancy firms.

For the implementation of the road dyke following the damage in 2012, the idea was far from realistic, he says. “I told the team responsible for welcoming President Paul Biya in 2012 that the proposed road dyke is like boiling seeds before sowing them. It’s something that won’t work. Firstly, in terms of maintenance. The road from Maga to Guirvidig is 24 km long, and we’re already having trouble maintaining that stretch; what more of maintaining 330 km?”, Mahamat says.

He recalls that the team deployed to consult the communities in the various villages came up against the same question every time: “The question that came up in almost every village was the role of the road dyke and its specific characteristics. People found it hard to answer. That is when I realized something fishy was going on. Communities were sold a dream,” says Aboukar Mahamat, who points out that the dyke-road project breaches the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance, ratified by Cameroon and Chad in 2006. “Cameroon and Chad have each included their portion of the Logone in the list of wetlands of international importance. This act obliges both countries to preserve its integrity and values,” he adds.

Constructing a road dyke would mean altering the hydrological state, which is contrary to the conventions that have been signed. Mahamat added that the project was unrealistic because it did not consider the spectacular geographical transformation of the Logone River given that in some areas, the river is within Chadian territory.

Joseph Junior Nyanda, an expert in risk and disaster management closely followed the management of the floods and says environmental aspects were not considered upstream.

‘The idea of a road dyke is not at all appropriate. You don’t deal with the problem by fighting nature but adapting to it because it cannot change. Instead of building this road dyke, we should have created canals that allow water to circulate and regenerate the soils rendered impermeable by human misuse. The regeneration of these soils will regulate the flooding problem in the area,” he explains, before questioning the implementation of the project.

The experts lacked the necessary experience to manage this type of project, and hastening to meet the challenges, they failed to conduct a strategic assessment of the entire Far North region including civil engineering, natural, environmental, and social solutions. Take Chad as an example: work to prevent floods within its boundary has remedied the problem, according to Joseph Junior Nyanda. Aboukar Mahamat agrees with this observation: “The project overlooked the population’s distinct traits. They are water people. People continue to stay and migrate to the Logone Plain because their earnings are a thousand times greater than their losses, especially during years of excessive rainfall. “The pasture, the fish, and when the waters recede in the dry season, there is a lot of rice production,” Mahamat recounts.

He remains convinced that the announcement to build the road dam was made without a proper preliminary study. “To a donor who is going to mobilize 1,000 billion to transform an ecosystem in the Lake Chad basin, it was impossible even when it was announced, from the point of view of feasibility. There has never been a project like this in a tropical wetland anywhere in the world,” the expert says.

He believes that it is vital to ‘talk with key stakeholders and professionals who know the area well to find the best approach so that these people who survive off water resources are not damaged in the event of excess floods,’ as he proposes.

FCFA 1 billion has already been spent on consultations for this project, which has not yet been implemented. The regional planning and sustainable development management scheme for the Far North, published in April 2024 by MINEPAT, projects that work on this road dam will be completed by 2035, with work progressing by 20% by 2027. However, it remains a mystery who will be carrying out the work and who will be the backers of this projection.

Emergency Flood Control Project (PULCI)

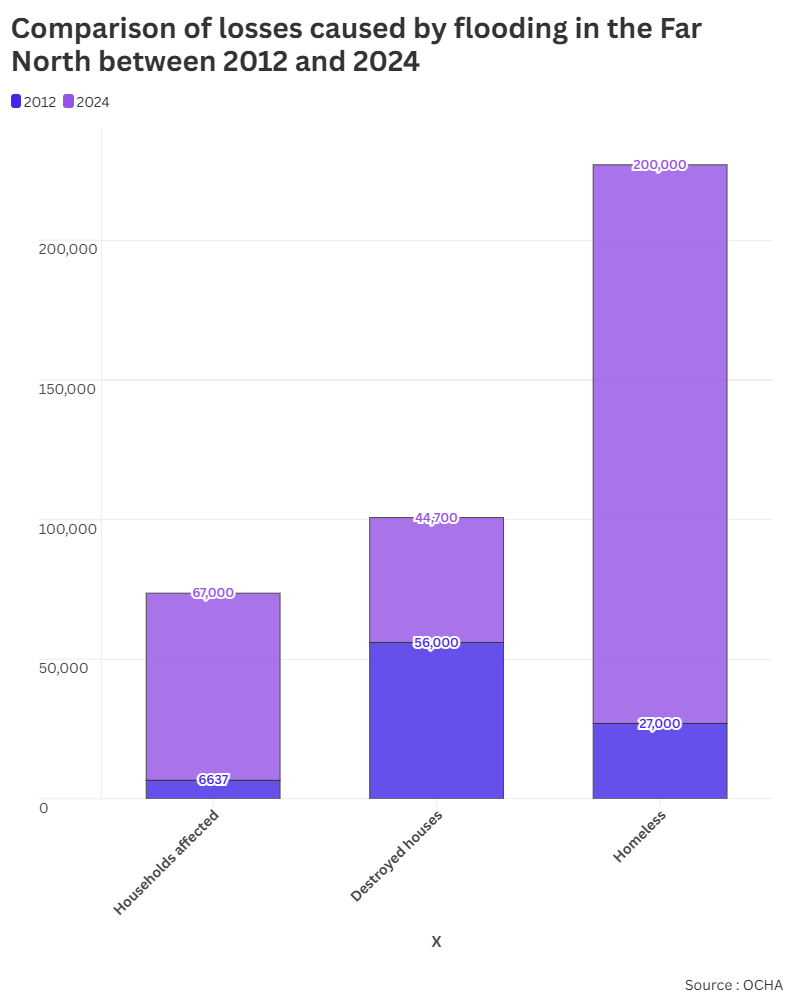

Following the floods in the Far North in 2012, it was projected that a dam failure may have floods around 150 km² and would endanger 120,000 locals. The rains and accompanying floods caused significant damage to the irrigation infrastructure of the Société d’Expansion et Modernisation de la Riziculture de Yagoua (SEMRY), destroying more than 25 kilometers of the Logone dyke. Around 60,000 individuals were affected, including 1,222 families in the Maga district and 9,025 families in the Logone and Chari districts.

President Biya visited Guirvidig and, in his speech on September 20, 2012, instructed, amongst others: “the rehabilitation of the Maga and Lagdo dams and an assessment of the cost of the destruction of homes, schools, roads and other infrastructure, road network, and other infrastructure, with a view to their immediate rehabilitation or reconstruction without delay.”

Against this backdrop, the Emergency Flood Control Project (Projet d’Urgence de Lutte Contre les Inondations – PULCI) was set up by the Cameroon government through the Ministry of the Economy, Planning and Regional Development to provide a lasting solution to the problems caused by the flooding in the Logone Valley.

The project, funded by the World Bank to the tune of $108 million (FCFA 56 billion) through the International Development Association (IDA), had the mission to rehabilitate the 27km Maga, 70 km-long Logone dyke and 7,500 hectares of SEMRY rice-growing areas. It was set to provide the intervention zone and the entire Logone catchment area with hydrometeorological equipment.

On the website of the World Bank in 2020 is an article titled, ‘Flood Management in the Far North of Cameroon: With the Rehabilitation of Logone Dyke and Maga Dam, Local Families Are No Longer Afraid of Heavy Rains.’ The completion of the dyke and dam prevented flooding in the area, allowing residents to sleep quietly without fear.

The balance sheet at the end of the project indicated the Flood Emergency Project was carried out between 2014 and 2020. “It restored 27 kilometers of the Maga dam, 70 kilometers (km) of the Logone dyke, and 7,500 hectares of irrigation systems. Additionally, training activities and job creation were offered by the project. About 103,000 people, including 30% women, and eight water-user groups directly benefited from the project,” the report published on November 10, 2020 reads.

However, twelve years later, the same population was woken up by floods in 2024, even with the hydraulic equipment in place. What could have gone wrong?

The people of Maga-47 villages expected the project to lay the groundwork for the road dyke and build residences out of durable materials. They expressed their disbelief as PULCI ended without them feeling the impact.

“Coming on the heels of the floods, PULCI ended without any real impact, without homes for the people affected by floods,” Ayang Hamadou, an elite from Maga, stated.

Djondandi Gourandi, an elder of Simatou, believes the main issue is drainage. “If there is proper canalization for water to flow smoothly, this could lessen floods in this area where we have our farms.” A lasting solution would be regional planning and drainage for water to flow into the Lake Chad basin, as the water in Maga comes from the Central African Republic and Adamawa region, suggested this elder from Simatou.

The government of Cameroon, based on what it considered the main achievements, lessons learned, and elements of capitalization from the Emergency Flood Control Project (PULCI), plans to rehabilitate the remaining areas.

To achieve this development objective in terms of improving irrigation services, rice production, and marketing in the irrigated areas of the Logone Valley, the Government has set up a new project, the Logone Valley Development and Investment Valorisation Project (VIVA-Logone), which is intended to continue, expand, and sustain the achievements of the PULCI.

The fruit of Cameroon-World Bank cooperation, the VIVA-Logone project has been running since November 2022, out of the projected seven-year life span, for a total of FCFA 124 billion. The project is structured around the improvement of infrastructure and water management, support services for agricultural production, institutional strengthening and implementation, and conditional emergency response.

Concretely on the ground, Viva Logone has a building constructed in Maga, and effective activities are billed to start in January 2025, according to the communication unit of the project.

Like many in Maga, Ayang Hamadou is worried that the project may not deliver, given the same team that carried out the PULCI project, is managing Viva Logone. He doubts the sincerity of the project, which, to him, could boost development in the region.

Construction of houses

Victims of the 2012 floods to date do not have homes in line with the instruction of President Biya for “an assessment of the cost of the destruction of homes, schools, roads and other infrastructure, road network, and other infrastructure, with a view to their immediate rehabilitation or reconstruction without delay.”

The location designated for the resettlement of flood victims in 2012 only contains 31 families; the remainder, like the inhabitants of Simatou, have returned to flood areas where they own farmland.

A report that Pulci built 3,639 comfortable housing units for 719 families against an initial target of 4,250 seems misleading. Laoumaye Merhoye, the former director of PULCI, in a WhatsApp conversation, said the author of the article could indicate where sources for the article were obtained.

He stressed, “PULCI activities, on the other hand, are financed by the World Bank-rehabilitation of 70km of Logone river protection dyke from Bidim to Mourla, rehabilitation of 27km of the Maga lake dam, rehabilitation of 7500ha of Semry irrigated perimeters and reinforcement of the hydro-meteorological network.”

“Resettlement is a prerequisite the Cameroonian government must meet before the project can be implemented.” He added. He states that the houses are financed by the government’s Public Investment Budget, BIP funds, and paid for by MINEPAT.

Another report indicated flood victims were to receive 200 houses, but it is not clear if the victims finally got the houses.

However, those who were provided homes are the people affected by the rehabilitation of the Maga dam and Logone dyke. The construction of the huts was partly entrusted under a Direct Agreement contract to Societe Sotcocog, a Tchadian company with the appropriate resources for this type of activity.

Natural Disaster Support fund

In 2012, the president instructed that a Natural Disaster Support Fund be established at the Ministry of Territorial Administration and Decentralisation for people affected by natural disasters.

This fund seems non-existent at the MINAT, sources are unaware of such a fund. They suggest the fund may exit with a different appellation.