“This story was produced with the support of Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.”

By Leocadia Bongben

Returning from the sea one morning in July with his catch, Nerville Eboma Ndomo, 25, is helped by young men and women at the Ebodje makeshift landing station. His wooden boat with a movable engine attached is pulled out of the water onto the sand for the women (whose main activity is fish smoking) to extract the fish entangled in the net.

Following in the footsteps of his forefathers as a member of the Iyassa clan of fishers in Ebodje, Ndomo, a student on holiday, is trying to perfect his fishing skills. This livelihood is shared by 80 percent of the Iyassa people of Ebodje village in the Southern part of Cameroon (370.9 km from Cameroon’s capital, Yaoundé).

“What I have here is sardine (bilolo). The catch is not good, but from mid-August, the peak fishing season is when the catch is excellent,” Ndoma says, adjusting his headlamp used at night to indicate presence at sea.

Ebodje, a fishing community of approximately 3,000 people, relies on sea products, such as sardines, and subsistence agriculture for survival. The community’s coastline forms part of the Manyange Na Elombo-Campo-a Marine Protected Area (MPA) that spans 110,300 hectares and encompasses 10 villages, including Ebodje. Here, the MPA lies in the Atlantic Ocean, along the maritime border with Equatorial Guinea.

Here, “The Iyassa people have a sacred link with water beings called ‘Mengu’ (mamiwata) and the sea turtle,” the custodian of the culture, His Majesty Ndjokou Djongo Christian Michel, third-class chief of Ebodje, explains. Equally important are the links with Manyange-Turtle and Elombo-Wolf-Rocks, sacred sites of the Iyassa people from which the MPA derives its name.

Ebodje is known for its turtles, which the people believe are ‘family members’, a great attraction for tourists, and the presence of other endangered marine species, such as whales and dolphins.

As of 2025, Cameroon has protected 11.1 percent of its marine areas, according to SkyTruth’s 30×30 Progress Tracker. This step is part of an ambitious goal agreed upon by nearly 200 countries in December 2022 at the UN Biodiversity Conference (COP15) to safeguard 30 percent of Earth’s natural areas by 2030. Cameroon is a signatory to this framework and has completed and submitted its national targets in accordance with its domestic strategy, NDS 30, and the Kunming-Montreal Global Goals.

Amidst the challenges facing the world’s oceans, including overfishing, plastic pollution, and rising sea levels, MPAs evolved as a solution for preserving marine life, supporting coastal communities, and contributing to the worldwide 30×30 target. To support this goal, national governments designate MPAs within their territorial waters, with input from scientists, conservation groups, and local communities.

However, achieving the 30 percent marine target seems elusive for Cameroon if the governance of the MPAs is not improved to protect marine biodiversity. According to experts, the procedure for designating the Manyange na Elombo-Campo as an MPA was not based on any scientific research, with no publicly available management plan in place when it was decreed.

“No research was conducted to support the creation of this MPA,” says Ndounteng Ndjamo Roderic Xavier, coordinator of the Tube Awu (Our Ocean), a Community Research and Development Association, with headquarters in Ebodje. The MPA was also created without a management plan, and consultation with the locals was carried out afterward, contrary to MPA guidelines.

Fretey, who later worked with NGOs, proposed a management plan with NGOs to the government, saying, “The Prime Minister’s Office and the Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife, MINFOF, are aware of the management plan but do not seem to care.”

Some members of the community are still unaware of the MPA’s importance and mission, and how it will affect their livelihoods. “Maybe the MPA will become like protected areas on land, where fishing will be prohibited. We are trying to understand the fate of the population in a fishing community like Ebodje,” says Mambo Emile Ebodje, fisherman and native of Ebodje.

Against this backdrop, the MPA faces several challenges — ones that the local communities are working hard to mitigate through participatory monitoring. Yet the protected area continues to face threats.

Manyange Na Elombo Campo suffocating?

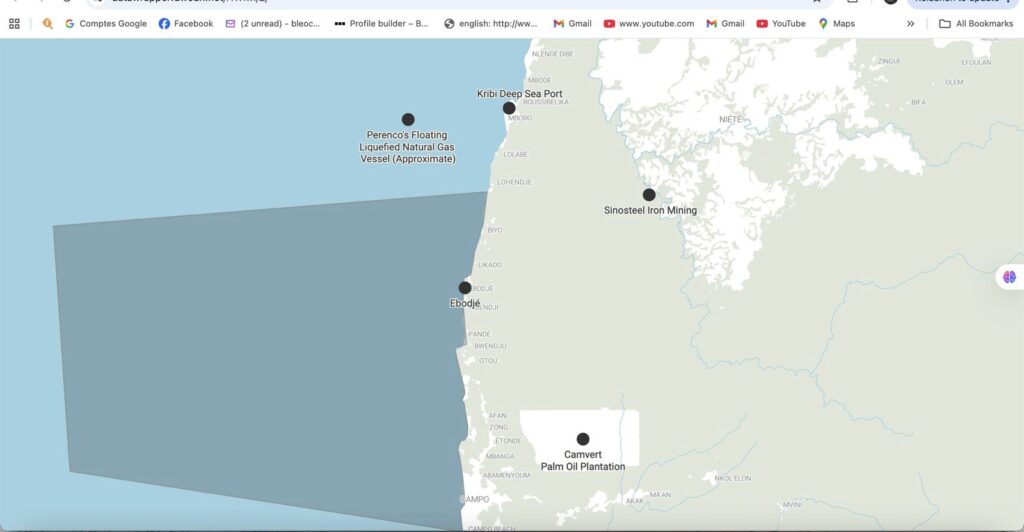

Despite the lofty objectives, 22.9 kilometers away from the border of the MPA, the Kribi deep seaport (constructed by China Harbor Engineering Company, a division of China Communications Construction Company Ltd. (CCCC), with its headquarters in Beijing) is impacting the MPA environment via light and noise pollution, trawler activity, and dike construction.

The environmental impact assessment of the port, conducted in 2021, did not state the number of kilometers surveyed, so it is unclear if evaluations were done close to the MPA border. The assessment indicated a shrinking coastline and the potential for increased pollution, but since the project was not within the boundary of the MPA, it did not halt construction.

The constant passage of ships close to the marine park creates noise pollution that is amplified in the water, says Joel Wanba Tchinda, an expert in the management of aquatic ecosystems, and Megafauna, Fish Programme Officer at Tube Awu. However, he adds that the influence on marine life has not yet been investigated.

So also, “The concrete bars in the sea modify coastal currents and amplify erosion, already visible at Ebodjé, where the coast has retreated by around fifteen meters in several places,” Fretey says. This corroborates a 2022 study depicting a weakening coastline and coastal erosion in the area.

A 2024 article in Mongabay cites a water pollution expert, Benjamin Ondo Obiang, who said in the article, “The more solid the infrastructure on the coast is, the more it activates the waves’ violence. As the sea becomes more aggressive, it destroys the coastal fauna and then the beaches. The entire biodiversity of this part of the coast is threatened.”

Fretey reveals that, “The port has already eliminated nesting sites and nursery areas for marine turtles, contrary to the requirements of CITES, the Bonn Convention, and the Abidjan Memorandum on Marine Turtles of the Atlantic Coast of Africa ratified by Cameroon.” (These are legal frameworks for the sustainable management of threatened aquatic and marine wildlife and habitats.)

Besides, industries threaten the marine ecosystem in the MPA. A local NGO, Youth for Promotion of Development, has indicated that the Sinosteel Cam SA (a subsidiary of the Chinese company Sinosteel Corporation) iron project may contribute to pollution by producing excessive dust, which could eventually deposit particles in the marine park.

Wanba, analyzing Sinosteel Environmental Impact Assessment, says, “There is no assurance that the dust, which is composed of heavy metals, won’t end up in the water, endangering both human and marine health.” There is also the potential for water pollution, Wanba explains. “The water to be used by Sinosteel is from the Lobe River ( 24.4 kilometers from Ebodje). When the minerals are washed, the water is likely to find its way into the MPA, as the sea sometimes moves up and down.”

Other threats loom nearby. Wanba says, Franco-British company Perenco, a liquified gas plant offshore, is 68.5 kilometers away. This may explain the “petroleum residue” Wanba says was found at the bottom of the marine park. Fertilizers and pesticides from Camvert, palm oil plantations 33.2 kilometers away, are likely to trickle down the river and into the sea, Wanba alleges. Aware of the difficulties facing sustainable and economic development, he suggests research must be carried out to produce concrete evidence for policy change.

Despite the challenges facing the MPA, Maha Ngalie, Director of Wildlife and Protected Areas at MINFOF, says in line with conservation strategies, the ministry envisages greater cooperation with the Kribi deep seaport and the industrial projects in the area. “An MoU is being drawn up between MINFOF and the Kribi deep seaport to limit the negative impact of certain activities on biodiversity,” Ngalie reveals.

Participatory monitoring helping Manyange na Elombo Campo

Hundreds of people rely on the waters and the coastal area of this MPA, making it a laboratory for participatory management. MINFOF drew up a document, titled “Guide to the involvement of local communities in the management of protected areas in Cameroon”, which was officially presented on 28 June 2024 in Limbé defining the role of local communities, as well as their involvement in the planning and decision-making process in the management of protected areas to guarantee the integrity of the areas and their enhancement with a view to local development. Communities adjacent to protected areas form committees and collaborate with the conservation office in managing the parks.

To breathe life into the MPA, Tube Awu, a Community Research and Development Association-NGO with headquarters in Ebodje (Fretey’s organization), the conservation office, and the community have been collaborating despite the lack of a government management plan and prior sensitization.“We (the conservation office) analyzed the threats and identified several activities to be carried out. We produced a charter for the sustainable management of resources,” says Patrick Maballa Sambou, the conservator of the MPA.

The stakeholders agreed on a charter, “ which provides for surveillance with the communities who fish in 24,000 hectares (of the protected area out of the 110,300 hectares), though not yet demarcated, and prohibiting fishing around the sacred sites.”

Drawing inspiration from the Iyassa culture, from July to August, called ‘Vilonda’- ‘the sea is angry’ (referring to storm season), the closed fishing season. The fishing gear called ‘wakawaka ’- a small-sized net was prohibited to prevent juvenile fish from being caught in fish reproduction zones.

“We no longer use the wakawaka nets, and following our tradition, we don’t fish at the Turtle and Wolf Rocks, our sacred sites. The conservation officer is… following our tradition, [which is] the reason we agreed to the closed season,” says Mambo Emile Ebodje, a fisherman.

Twice a month for two and a half hours, a team of eight people, including eco-guards and community members, goes on a boat monitoring. This was supported by the Cameroon Wildlife Conservation Society (CWCS, whose initiative, funded by Oceans 5, provided a speedboat with a 40 KW engine and GPS to the conservation office.

Eugene Diyouke, interim coordinator of CWCS, says, “We are enhancing the MPA’s ability to provide conservation services along the coastline of Douala-Edea and Manyange Na Elombo Campo. The project also focused on producing a management plan and other documents to improve protected area management.”

Also, thanks to training from the African Marine Organization (AMMCO), the conservation office now uses Global Fishing Watch tools to monitor trawlers fishing in the MPA. “We gather information on the trawlers, the name of the company, and the owners, but can only see incursions after and not before, therefore, [we are] unable to stop the trawlers,” says Sambou.

In terms of potential Tube Awu, an ongoing process has identified about 40 fish species, 12 of which are listed on the IUCN Red List as species on the verge of extinction, including sharks, whales, dolphins, and rays.

Joel Wanba, an aquatic expert and Megafauna Programme officer at Tube Awu, says that through a participatory science program from September to May in 2023 and from September to November in 2024, fishers collect data at the landing station, including descriptions, lengths, sizes of the caught species, and the nets used. This provides Tube Awu with information about the level of resource exploitation, the current stock, and fishery sustainability.

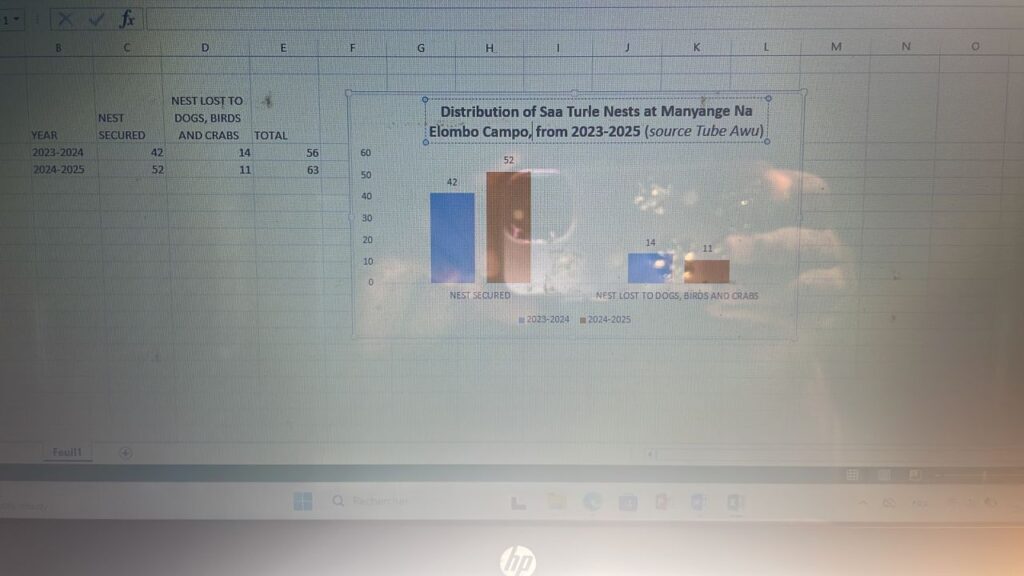

Two species of sea turtles (olive ridley, leatherback, green, and hawksbill) lay eggs at the MPA, while others feed there from September to May. During this time, Tube Awu and the community increase their surveillance. This NGO trains and remunerates community members who clean and monitor the MPA beach, keeping an eye out for potential turtle feeding grounds, identifying nesting sites, and transporting eggs to the nursery.

Monitoring contributes to gathering data about sea turtles and their egg-laying environment, which helps to lower the risks posed by dogs and crabs. “When the young turtles are mature enough to lay eggs, they can return to the beach,” according to Yves Maximes Mondjeli Ndjokou Djongo, Sea Turtle Programme Officer at Tube Awu.

“The park provides us with employment during the egg-laying season, we are recruited to patrol the beach and gather the eggs to protect them from crabs and dogs… We now know how to place the eggs in the same way the turtle left them,” says Ebodje, adding he is eager to make money from monitoring the beach to protect the sea turtles.

“Not only do some of us take part in protecting the sea turtles, but we also sensitize our community not to eat turtles that we accidentally catch in our nets, we report to the conservator, and they are released into the sea, or the dead are authorized to be eaten,” says Ela, a fisherman in Ebodje.

Tourists are drawn to the turtles. Ela continues, “We have the Ebo Tour (a community lodge) to lodge people who stay and watch the turtles arrive, dig, and lay their eggs.”

Challenges remain

Despite the potential of the MPA, Wanba says Tube Awu has observed a decrease in fish. In 2014, 44 species were identified, and in 2025, 32 fish species were identified during the same period and in the same zone.

“The number of sea turtles has decreased from the previous season,” Mondjeli says, despite releasing 30,000 turtles back into the ocean since 2015. 56 nests were found during the 2023–2024 season; 42 were secured, while 14 were lost to dogs, birds, and crabs. The 2024–2025 season also saw the identification of 63 nests, 52 secured, and 11 lost to birds, dogs, and crabs.”, Mondjeli reveals.

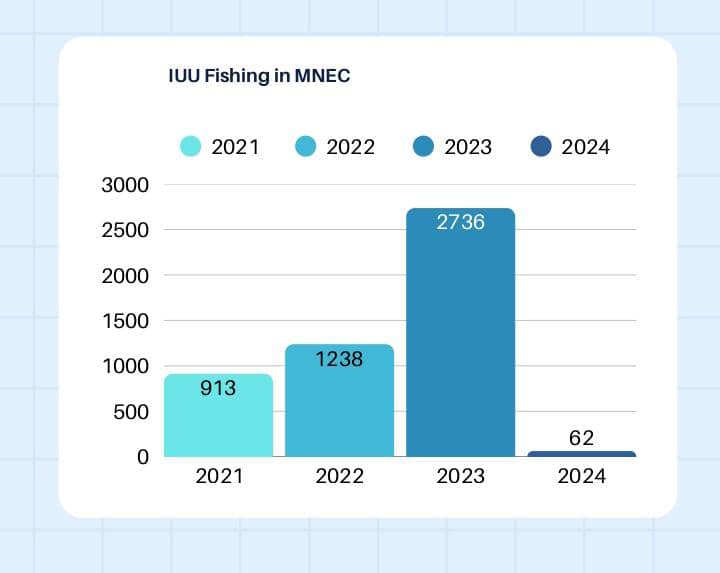

There may be fewer trawlers—three entered the park so far between 2021 and 2023—yet technological barriers still pose problems for enforcement. For the past two years, the same three trawlers—Nicolas, Adonia, and Erica 1—have fished in the park. These are Cameroon-flag vessels, but it is difficult to determine the owner. “Signals of trawlers were detected this year, but we were unable to determine if they were coming from fishing trawlers since they concealed their location and turned off their GPS,” Sambou adds. Global Fishing Watch data identifies vessels within the MPA from June 1 to August 30, 2025, for up to five hours, but it is challenging to determine their fishing status

“Within 48 hours, we can use TravelMarine to scan the database and determine who went fishing. We can’t go very far; the fishermen are our eyes and ears,” Sambou says.

The presence of several fish species in Manyange Na Elombo Campo and the entire coastal zone, such as threadfins, croackers, catfish, and sardines, attracts commercial trawlers. Eighty percent of local fishermen’s catch in 2018 came from sardines, absent last season, Wamba says.

A sonar-sound kit investigation by Tube Awu reveals an impact on the sea structure, including mangroves, grasslands, and coral reefs, in areas of illegal fishing, according to Wamba.

Because the official MPA decree only states the objective of limiting the incursion of fishing trawlers, there is little enforcement capacity. For instance, there are no financial penalties for trespassing in the MPA or illegal fishing, and the complaints from local fishermen about trawlers destroying their nets with their catch seem not to attract government action.

“The conservation office intends to provide fishermen with cellphones so they can record illegal fishing activities using the GPS coordinates as evidence,” Sambou says. “[And] planting buoys to demarcate the MPA and the area reserved for local fishers.”

He added that the government intends to produce an official management plan, “which may raise the protection level of the MPA”. Maha Ngalie, Director of Wildlife and Protected Areas at MINFOF, says, “The Management Plan will be drawn within the African Development Bank AFDB project to improve the resilience of riverside communities in the area between the mouth of the Ntem and the mouth of the Wouri.” The bank agreed to finance the project, and though communities would be involved, the timeline is not yet known.

Jacques Fretey, sea turtle expert, says he attempted to include a site of international interest, Chutes de La Lobé, in the MPA designation but was refused. “It would have been possible, once the port had been created, to create a marine bridge between the marine park and the Chutes, with the port paying a toll to each boat crossing this marine line. Elsewhere in the world, a similar tax system exists between an MPA and the installation of a port adjacent,” says Fretey.

With only five years until 2030, it remains to be seen whether the future management plan to be developed in consultation with the community will lessen concerns of fishing restrictions, improve governance, and increase community involvement in Manyange Na Elombo-Campo MPA.